Solexa

Solexa has come up in a few conversations recently. Obviously Solexa’s contribution to next-gen sequencing is difficult to ignore. But it’s also an interesting case study in how tortuous the route to commercial success can be.

So while I’ve written about Solexa before I thought it might be interesting to revisit the company. Particularly in light of some interesting quotes from the recently released The Genome Odyssey.

Solexa was founded in 1998. They were funded by Abingworth Bioventures, a few hundred thousand at first, then £1.5 million, and later a £12M round in 2001. At this point they described themselves as a single molecule company.

In 2004, Solexa and Lynx Therapeutics Inc. jointly acquired Manteia’s cluster generation (bridge amplification) technology. I’ve written about Manteia before and it looks like this acquisition was for a few million dollars. Given how drastically this technology changed the sequencing market, this seems absurdly low.

This acquisition appears attracted John West as the The Genome Odyssey describes:

“By the time a member of Solexa’s board reached out to John in 2004, he was with Applied Biosystems, a company specializing in automated Sanger DNA sequencing using fluorescent technology—and whose low-throughput technology was the workhorse of the Human Genome Project. The voice at the other end of the phone asked him if he had heard of a company called Solexa and if he might be interested in a job as its CEO. He understood the fluorescence-sequencing technology invented by Solexa but was unclear how they could produce sufficiently reliable fluorescence signals from single DNA molecules, so he turned the offer down. It wouldn’t require a large increase in the fluorescent signal to achieve reliable imaging, he figured, perhaps only one or two orders of magnitude, but Solexa simply didn’t have the goods. A few months later, however, he learned that Solexa had licensed technology from a company called Manteia for creating DNA clusters—small “islands” of DNA on which around one thousand identical DNA molecules could be simultaneously “grown.” This caught John’s attention. In comparison to a single DNA molecule, the cluster technology could increase a fluorescent signal by three orders of magnitude. In fact, John had previously encouraged Applied Biosystems to buy that same technology, suspecting it could be transformative to sequencing, but the leadership hadn’t been interested. When he saw that this small British biotech had acquired the rights, he called back their chairman. “Do you still need a CEO?” he asked.”

The Manteia cluster generation approach did indeed turn out to be transformative. Without this Solexa may well have ended up looking a lot like Helicos (and its various less than successful reboots).

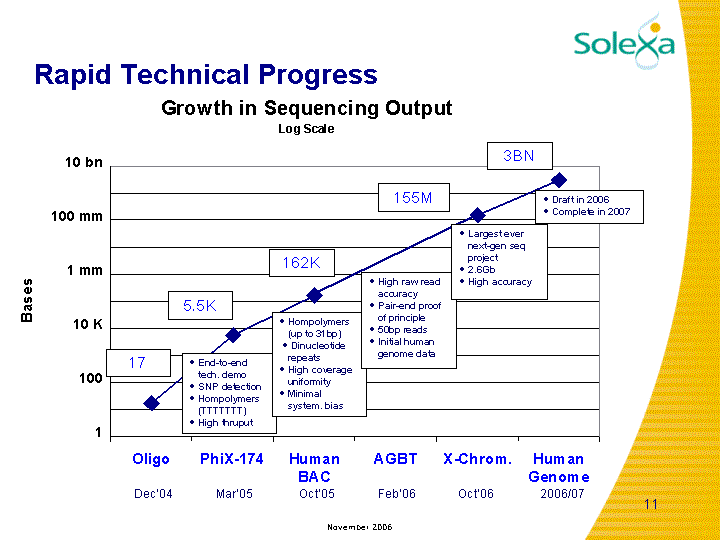

Post acquisition, Solexa made rapid technical progress as the following slide from Illumina’s SEC filings shows:

In 2005 Solexa was acquired by Lynx Therapeutics, Inc. The deal gave the combined entity (renamed Solexa) a US stock listing.

At this point Solexa were well positioned to starting to pump out instruments. These were little more than lab rigs using largely COTS/OEM components in a custom enclosure:

The optical system used a prism-style TIRF imaging system, probabily for historical reasons. Later instruments (Hiseq) abandoned the TIRF approach.

Illumina acquired Solexa in 2007 for $600M. Which, given we now see IPOs and acquisitions in the billion dollar range pre-product, seem like a bargain.

While the Genome Analyzer wasn’t the most reliable of instruments, Illumina had a few relatively large deployments. The Sanger institute had ~20 and proudly boasted hitting 1 Terabase with these instruments.

In 2010 Illumina came out with the Hiseq 2000, a more reliable and better engineered instrument. They dumped the TIRF imaging system and moved to Hamamatsu TDI image sensors. This line of instruments iterated toward the Novaseq class of very high throughput sequencers. Along the way adding exclusion amplification, and super resolution imaging to further push throughput.

A second product line (the Miseq) was introduced in 2011. These lower throughput instruments are a lot more similar to the original Solexa platform. They use cheap consumer grade image sensors (Sony full frame sensors from DSLRs).

While other iterative improvements have been made, the basic approach is largely unchanged. This makes the run up to 2024, when the last of the original Solexa IP is set to expire all the more interesting.